After the US withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021, the Taliban swiftly regained control of the Afghan government. The country faces profound challenges, including economic decline, humanitarian crisis, governance issues, rising security threats, and global isolation due to sanctions and nonrecognition. Although the Taliban are in power in Afghanistan, all these issues are not their doing. Over the past two decades, the US and NATO have made significant investments in Afghanistan, yet the country’s infrastructure and stability are precarious. This insight establishes that the primary responsibility for Afghanistan’s ongoing instability lies with the US-led West, whose actions and policies during the War on Terror suggest lack of commitment to fostering stable Afghanistan.

One of the main factors contributing to Afghanistan’s ongoing instability is the nonrecognition of the Taliban government as a legitimate or sovereign authority by world capitals. This has led to Afghanistan's diplomatic and political isolation, denying Afghan representation in international fora. The UN credential committee has rejected the Taliban regime's request to acquire the assigned seat for Afghanistan’s representative at the UN several times.

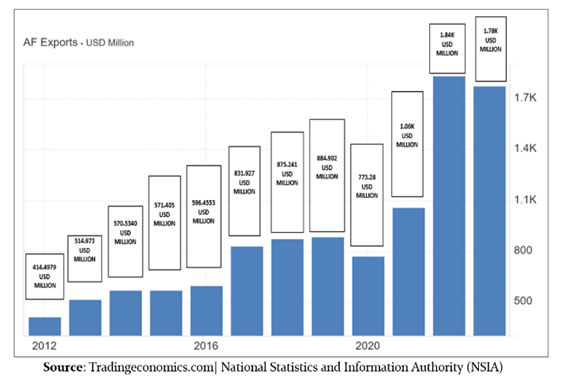

The economic sanctions imposed by the US, UN, and EU have exacerbated Afghanistan's economic woes, restricting its international trade. The US froze nearly US$9.5 billion of Afghanistan’s external reserves, leaving the Afghan central bank, Da Afghanistan Bank (DAB), asset-deprived and cut off from the global financial system. The World Bank estimated that Afghanistan's real GDP declined by approximately 26% in 2021 and 2022. Exports from Afghanistan decreased to US$1777.90 Million in 2023 from US$1837.56 Million in 2022. This persistent economic isolation underscores the US and NATO's lack of interest in transforming Afghanistan's war-stricken economy into a sustainable one despite their two-decade presence and substantial investment.

Despite the presence of the US and NATO for two decades, no substantial effort has been made to transform Afghanistan's economy or to leverage its strategic potential as a regional trade hub connecting Central Asia to South Asia and the Middle East.

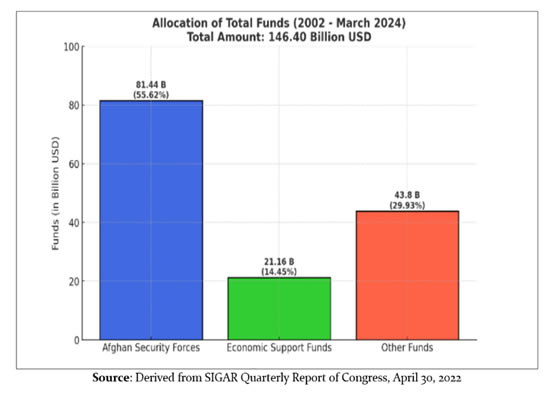

Furthermore, The Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) quarterly report dated April 30, 2022, states that the total amount appropriated for reconstruction efforts in Afghanistan from 2022 to March 2024 was US$146.40 billion. Out of this, US$81.44 billion was allocated to Afghan security forces, representing 55.62% of the total reconstruction funds, while US$21.16 billion was allocated to the Economic Support Fund, accounting for 14.45% of the total. This lack of prioritisation during a period of significantly available international resources and focus reflects NATO's disinterest in addressing Afghanistan's structural economic issues, which perpetuate its dependency on a ‘War Economy’. It would not be wrong to say that Afghan institutions failed to sustain themselves because a significant portion of US funds was directed toward military spending rather than critical infrastructure development, capacity building, and human resource development, as illustrated in the graph below.

The 2020 Doha Agreement, primarily aimed at the smooth US withdrawal, had significant flaws. It excluded the Afghan government from negotiations, undermining the agreement’s legitimacy, and lacked a clear political roadmap for peace. The rushed US withdrawal left Afghan security forces unprepared, turning the agreement into a tool for the US expedited exit rather than a lasting solution. The establishment of the Taliban government as a result of the Doha Agreement and US withdrawal paved the way for Afghanistan to become a haven for terrorist organisations like Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), Tehrik-i-Jihad Pakistan (TJP), Jamaat-ul-Ahrar (JuA), Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA), Islamic State in Khorasan Province (ISK-P), East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), and other militant organisations.

In other words, the US-led West is directly responsible for the presence of terrorist organisations threatening regional peace and stability. These terrorist organisations, besides obstructing the integration of Afghanistan into China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), also threaten CPEC-the flagship project of BRI.

A significant fallout of the instability in Afghanistan has been the unchecked influx of US-made arms and ammunition into Pakistan. As reported by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty in March 2023, a staggering US$7.2 billion worth of military equipment, including aircrafts, guns, vehicles, night vision goggles, and biometric devices, was left behind in Afghanistan by the US and NATO. This equipment, previously under the control of the Afghan National Defence and Security Forces (ANDSF) and supplied initially and managed by the US and NATO, has found its way into the hands of non-state militant groups, including the TTP, BLA, and other terrorist groups, fueling cross-border terrorism.

As a result, TTP attacks have surged by 27% and BLA attacks by 36% since the Taliban's takeover, intensifying Pakistan's national security risks. This alarming situation underscores how the unregulated transfer of arms and ammunition across the Afghan-Pakistan border has exacerbated the threat posed by non-state actors, highlighting the broader regional repercussions of the US exit.

Afghanistan's history of foreign invasions and the presence of the Taliban have left the nation in a fragile state. Despite two decades of presence and substantial investment, the US failed to prioritise the creation of a stable and sustainable Afghanistan, leading to the recent instability post 9/11.

Therefore, the responsibility for the recent instability in Afghanistan (post 9/11) squarely lies with the US-led West, whose policies and actions were contradictory. It is pretty evident that within the realms of contemporary geopolitics, characterised by the predominant factor of the US-China rivalry, it is in the larger strategic interest of the US to keep Afghanistan destabilised to prevent China from dominating the region in its proximity through trade and connectivity corridors like the BRI. What remains to be seen is how China and, to some extent, Russia will respond to this US disruption strategy in the region characterised by the ‘constructive chaos’ theory.

The views expressed in this Insight are of the author(s) alone and do not necessarily reflect the policy of ISSRA/NDU.