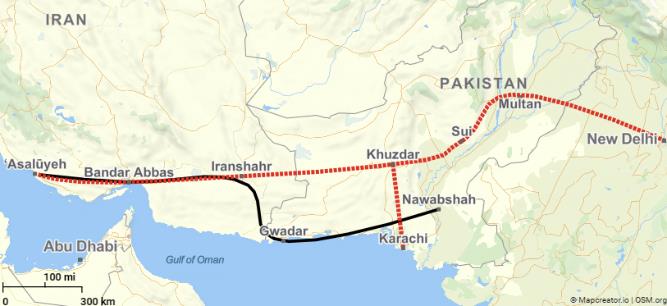

In 1995, a tripartite agreement was signed between Iran, Pakistan, and India, called the Iran-Pakistan-India (IPI) Gas Pipeline project. However, after 13 years, in 2008, India withdrew from the project on the pretext of US sanctions on Iran. Subsequently, in June 2009, Pakistan entered a separate Gas Sale and Purchase Agreement (GSPA) with Iran, initiating the Iran-Pakistan (IP) Gas Pipeline Project. This project will provide Pakistan with 750 MMcf/d to 1.05 Bcf/d of natural gas from Iran’s South Pars Gas Field. Under the GSPA, the pipeline's total length is approximately 1,953 km. Iran is responsible for constructing and operating 1,172 km from the Pars Economic Energy Zone at Assaluyeh to the Iran-Pakistan (IP) border. Pakistan will build and operate 781 km of the pipeline from the IP border to Nawabshah.

The pipeline was to be completed by 2014. While Iran claims to have completed its portion by 2012, Pakistan failed to begin construction until 2014. In March 2014, Pakistan served force majeure notice to Iran under the GSPA, citing US sanctions on Iran as events excusing it from completing the project. Iran rejected the notice but extended the deadline for completion by an additional decade to March 2024. In February 2024, Pakistan’s interim government approved the construction of an initial 80 km section from the IP border to Gwadar as a last-minute effort to avoid legal action by Iran for noncompletion. This move earned Pakistan an additional 180-day extension, pushing the deadline to September 2024.

Figure 1: IPI Gas Pipeline [Red] |IP Gas Pipeline [Black]

Since the project’s inception in 2009, Iran has served Pakistan three notices under the GSPA. In February 2019, the first signalled Iran’s intent to initiate arbitration and invoke the penalty clause. In November-December 2022, the second issued an ultimatum for Pakistan to either complete its portion or face US$18 billion in penalties. In August 2024, the third notified Pakistan of Iran’s intent to approach the Paris Arbitration Court in September 2024 for failing to meet the extended deadline. Under the arbitration mechanism, the last notice is legally termed a ‘Notice of Dispute’. This insight discusses the implications of Iran’s notice under the IP Gas Pipeline project and the legal options available to Pakistan.

Given the circumstances, Iran’s notice to Pakistan could have far-reaching implications, the most imminent being potential multibillion-dollar arbitration proceedings. Should Iran proceed and ultimately succeed, Pakistan could face 18–US$20 billion in financial liabilities. This sum would cover interest, penalties and damages for Iran’s losses from the pipeline’s non-completion, lost revenue, arbitration costs, etc. In 2023, Pakistan’s GDP was $338 billion; therefore, this financial liability would represent almost 6% of the total GDP—an unbearable burden on Pakistan’s recovering economy.

Most importantly, this dispute could leave Pakistan energy deficient as demand increases and reserves deplete. Natural gas accounts for 33.1% of Pakistan’s total energy consumption. In 2022, indigenous gas production accounted for 73.6% of the total supply, but it had decreased by over 6% to 2,006 MMcf/d from 2,138 MMcf/d. Net gas imports, on the other hand, make up 26.4% of the total gas supply. With gas demand projected to reach 1,431 Tcf by 2025 and 1,576 Tcf by 2030, the IP Pipeline was meant to provide a stable supply, mitigating an energy crisis.

Alternatively, this dispute could impact Pakistan’s other transnational projects, like the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) Pipeline. It raises concerns about Pakistan’s commitment to completing such projects, signalling to regional actors that Pakistan may similarly struggle to meet its obligations under these initiatives.

Given these implications, Pakistan has a few options. The first option would be to construct the pipeline, which would be more favourable than arbitration overall. However, US sanctions on Iran pose a significant obstacle—not in building the pipeline but in purchasing Iranian gas. To avoid violating these sanctions, Pakistan could follow the example of Iraq and Türkiye, who have secured waivers from US sanctions to import gas from Iran. Alternatively, Pakistan could bypass paying in US$ by using an alternative currency, like the Chinese Yuan, or by employing a barter system. Under a barter arrangement, Pakistan could exchange goods or services of equal value with Iran, thus sidestepping the need for currency payments and easing compliance with sanction restrictions.

If construction is not considered, Pakistan’s second option is arbitration. Iran has only issued a ‘Notice of Dispute,’ which signals a disagreement under the GSPA but does not initiate arbitration. This typically invites amicable dispute resolution before moving to arbitration.

For arbitration to formally begin, Iran must serve Pakistan with a ‘Notice of Arbitration’. Therefore, Pakistan does not need to readily respond by stating its defence. Instead, it could request Iran to negotiate or approach third-party mediators like China, Russia, or the OIC to prevent the dispute from escalating and straining geopolitical relations.

Nonetheless, Pakistan can adopt a different approach if the arbitration proceedings commence. The dispute resolution mechanism under the GSPA is governed by the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules, with French Law as the governing law and Paris as the seat of Arbitration. Firstly, if there is any irregularity or ambiguity in the arbitration clause under the GSPA, Pakistan could challenge the arbitral tribunal's jurisdiction.

Secondly, the French Arbitration Court does not recognise US sanctions. At the jurisdictional challenge stage, Pakistan could argue that this is against its public policy, i.e., the state where enforcement of the award would ultimately be sought. Alternatively, if the award is rendered against Pakistan based on this rationale, Pakistan can challenge its enforcement in local courts because it violates domestic public policy. If successful, the local courts may refuse to enforce the award.

Thirdly, regarding the US sanctions, Pakistan could invoke a force majeure defence, combined with hardship and changed circumstances defence under French Law, to argue that the sanctions have created an impossibility that prevented Pakistan from fulfilling its obligations under the contract.

The IP Gas Pipeline Project remains one of Pakistan's most controversial yet economically crucial projects. Although Iran’s notice to Pakistan does present significant implications, it is not a dead end. Pakistan could move forward with construction under alternative payment methods, negotiate a waiver from US sanctions, or, if necessary, approach arbitration with a well-prepared defence. Each step carries its challenges, but with a balanced approach, Pakistan could find a solution supporting economic stability and regional cooperation.

The views expressed in this Insight are of the author(s) alone and do not necessarily reflect the policy of ISSRA/NDU.