Vietnam’s geopolitical significance is deeply rooted in its strategic geographical location along the South China Sea. This location, a crucial maritime gateway in Southeast Asia, has historically made Vietnam a focal point for major global powers aiming to exert influence in the region. Vietnam has effectively managed its relationships with international and regional powers, stimulating economic growth and increasing its strategic importance. This adept handling of major power dynamics has allowed Vietnam to attract significant investments and expand trade opportunities, thereby driving its development in both geopolitical and economic terms.

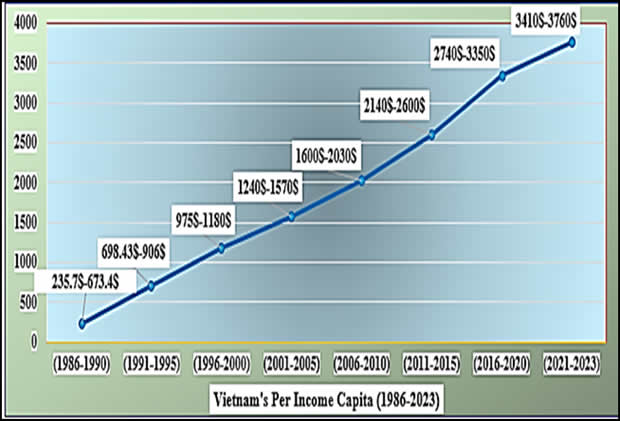

Vietnam's transformation from an impoverished economy to one of the world's fastest-growing economies is a testament to the power of strategic reforms. This journey began in 1986 with the Doi Moi (Renovation) reforms, which aimed to enhance the private sector's role and attract foreign investment, transitioning Vietnam from a centrally planned economy to an open market. At the same time, political stability and consistent leadership have underpinned these reforms. The Vietnamese government's maintenance of a predictable political climate has minimised social unrest and political turmoil, creating a secure environment for economic activities and investments. State-owned enterprises were significantly reduced, fostering the growth of private businesses. The combination of political stability and economic reform has been instrumental in curbing inflation and sustaining high growth rates, illustrating the critical role of a stable political environment in achieving financial success.

Figure-1: The graph shows Vietnam's GDP per capita increased twelvefold from 1986 to 2023 because of these economic reforms

In 1994, the US lifted its trade embargo on Vietnam, opening the country to join the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA). The lifting of the blockade was a strategic move by the US to counter China's influence in the region. Another significant milestone in Vietnam's economic journey was signing a free trade agreement with the US in 2000. Its membership followed this in the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2007, significantly reducing tariffs and enhancing trade relations with several countries. The subsequent signing of crucial trade agreements, such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement (EVFTA), further expanded Vietnam's market access, investment opportunities, and technological breakthroughs. These agreements focused on reducing tariffs and enhancing intraregional trade underscore Vietnam's feasibility of leveraging global alliances.

The US and EU have taken advantage of Vietnam’s economic reforms by diversifying their supply chains and reducing reliance on China. Since 2010, the similarity in export destinations between China and Vietnam has significantly increased. This shift is mainly due to Vietnam reorienting its exports towards the US and EU through trade agreements like EVFTA and CPTPP. Vietnam's exports to the US have seen rapid growth of US$123.5 billion, constituting approximately 30% of Vietnam's total exports and 19% of its exports to the EU.

Figure-2: Graph shows the Exports/Imports Volume of Vietnam with China, US, EU, UK and ASEAN

On the other hand, Vietnam and China have also maintained a comprehensive strategic partnership since 2008. The graph shows that China remains Vietnam’s largest trading partner, with bilateral trade growing from US$12.15 billion to US$175.7 billion. China's strategic investment in Vietnam aims to diversify its manufacturing capabilities, sustain economic influence, and strengthen regional interdependencies amid ongoing geopolitical tensions with the US while safeguarding its economic interests effectively.

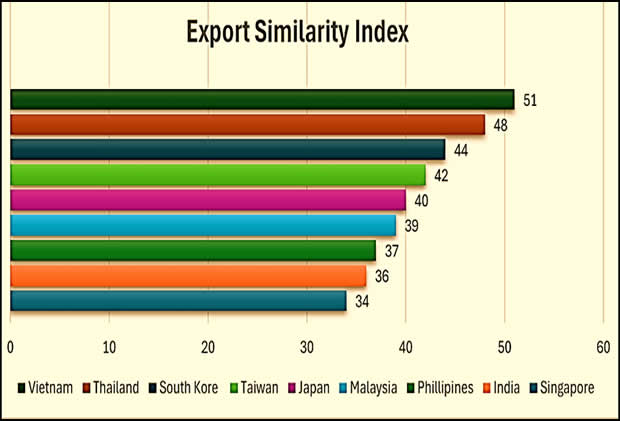

Figure-3: Vietnam's exports exhibit 51% similarity to those of China's Export

The ongoing trade war between the US and China has led multinational corporations to adopt the 'China plus one' strategy, which involves maintaining operations in China while expanding production to other countries like Vietnam. Vietnam's attractiveness as a substitute is evident in its ranking first in the export similarity index with China, with a 51% export similarity. The US is leveraging this high export similarity index to diversify supply chains away from China, enhancing resilience and reducing dependence. As part of this strategic shift, the US introduced the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a trade agreement centred around the US and excluding China. This shift resulted in a surge in FDI, reaching US$27.72 billion in 2022, solidifying Vietnam's role in global supply chains and as a critical player for the US to counter China’s influence in the region.

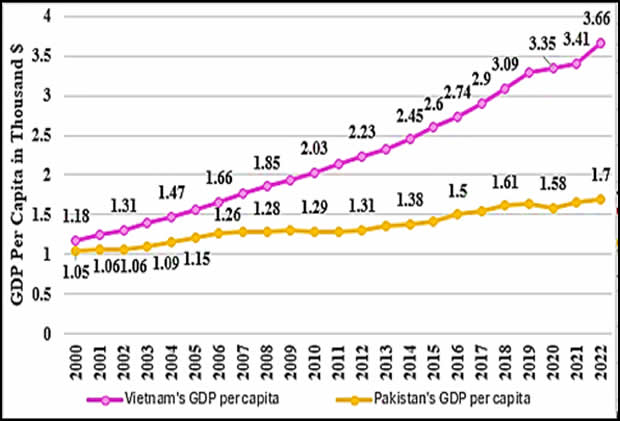

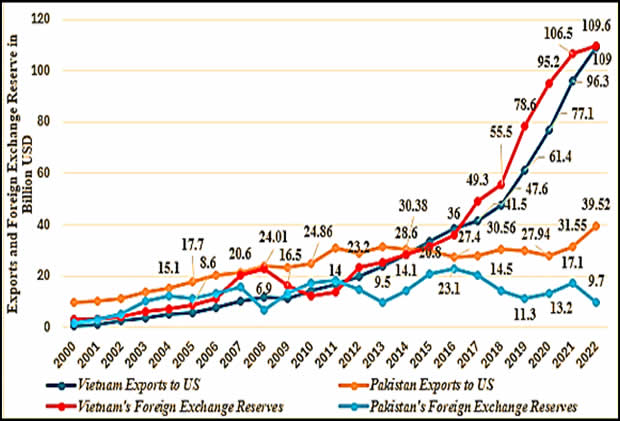

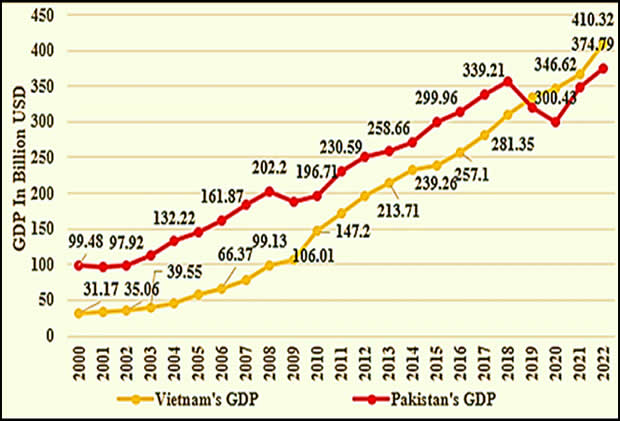

Turning to a comparison of Pakistan and Vietnam's economic trajectory over the years, the following graphs represent a comparative analysis of both countries' foreign exchange reserves, exports to the US, GDP, and GDP per capita from 2000 to 2022. Over this period, Vietnam has followed a distinct path, with its foreign exchange reserves and exports to the US showing significant growth compared to Pakistan. Vietnam’s GDP surpassed Pakistan's from 2007 onwards. Similarly, Pakistan's GDP per capita has consistently remained lower than Vietnam's, underscoring the countries’ economic well-being differences.

Graph-1

Graph-2

Graph-3

The dissection of Vietnam’s economic rise indicates that post-Cold War, only those countries who aligned themselves geopolitically with the US-led West or vice versa witnessed significant economic development. Although one can say that Vietnam introduced multiple initiatives in the late 1980s, such as economic reforms, political stability, and continuity of policies, it is also a fact that the catalyst moment remains their opening of diplomatic ties with the US in 1994. Similarly, India is another country that witnessed an unprecedented economic rise post-Cold War because its global relevance aligned with the geopolitical interests of the US-led West or vice versa. No wonder, today, the US calls India the net security provider in the region to counter China. It is important to note that Vietnam and India were neither geoeconomically nor geopolitically aligned with the US-led West during the Cold War. Indonesia is another example which remained largely non-aligned but swayed on both sides during the Cold War.

The disintegration of the former USSR and the eventual rise of China forced the US to find new strategic partners in Asia-Pacific to counter the emerging geopolitical challenge to its global supremacy. South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Philippines, Singapore, Malaysia, etc., were already part of the US-led West, so the US concentrated on bringing Vietnam, India, and Indonesia towards its corner. Since the US had little economic and political stakes in these countries during the Cold War, all three countries also managed to maintain relatively cordial relations with the US adversary, i.e. China. The primary reason for the ability of these countries to successfully hedge between the US and China was the US compulsion to increase its ‘stakes’ in these countries and not vice versa. Therefore, one notices a visible shift in the economic growth trajectory of all these countries, especially Vietnam, from the former USSR and later from China to the US-led West in the 1990s and more so at the start of the new millennium. However, once the US has firmly established its economic and political stakes in these countries, it would be possible for the US-led West to manipulate these countries' economic and political environment.

In the case of Pakistan, the situation is rather interesting. During the Cold War, Pakistan was aligned with the US-led West regarding geoeconomics and geopolitics. As soon as the Cold War ended, Pakistan lost its geopolitical relevance to the US-led West against China because the latter found India to be a preferable strategic partner against China, given its size, population, geography, etc. Whereas Pakistan tried to find geopolitical refuge with a reluctant China, geoeconomically, it remained anchored with the US-led West, which created a tremendous strategic vulnerability for Pakistan. Until today, Pakistan has yet to find its proper place and role within the context of US-China rivalry. On one hand, geopolitically, it tilts towards China and Russia. Still, on the other hand, geoeconomically, it cannot free itself from the clutches of the US-led West. It must be remembered that, in strategic terms, the US-led West has chosen India as its partner against China. For them, Pakistan is perhaps a potential ‘spoiler’, which enjoys closer ties with China. Hence, it seems that an economically fragile, sociopolitically weak and vulnerable Pakistan serves more extensive strategic interests of the US-led West in the region.

Above all, Pakistan needs to determine its proper role and place in the geopolitical circus of the US-China rivalry. One option could be to work towards an alternate economic paradigm wherein Pakistan focuses on its “Pivot to Geoeconomics” despite geopolitical challenges, as outlined in the National Security Policy 2022-2026. This implies that Pakistan needs to crystallise and list its economic priorities and pursue them fully, utilising all elements of national power (EoNP). In this process, Pakistan should seek the support of the US and China, wherever it serves its national interest, to exert its actual strategic weight in the region. At the same time, Pakistan should continue doing business with the US, the UK, and the EU. It must try to diversify its export markets according to an economic roadmap. For example, if the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) gas pipeline or the Iran-Pakistan (IP) gas pipeline makes economic sense, then Pakistan must utilise all EoNP to complete these projects despite geopolitical challenges. Since the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and serves own national interest, Pakistan must go for it despite all internal and external challenges. Similarly, if trade with India and Iran is beneficial, Pakistan should also consider it a strategic priority despite fear of sanctions.

In short, Pakistan must outline its economic priorities clearly while keeping the general public confident about the enormous opportunities and dire challenges. This requires a coordinated effort utilising all EoNP. Pakistan needs to build an alternate economic paradigm wherein instead of looking towards the US and China for financial bailouts, the world and regional powers should look towards Pakistan as a game changer.

The views expressed in this Insight are of the author(s) alone and do not necessarily reflect the policy of ISSRA/NDU.